All Hallows Eve: The Backstory

November 1, 2022

Halloween, or also known as All Hallows Eve, can be traced back to the ancient Celtic festival known as Samhain (pronounced sow-in), which was held on November 1st. The Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago, mostly in the area that is now Ireland, the UK, and Northern France, celebrated their new year on November 1st. This day marked the end of Summer, the harvest,the beginning of the dark-cold-winter. This time of year the Celts often associated with human death. It was believed that on this day, the souls of the dead would return to their home for one day, so people dressed in costumes and lit bonfires to ward evil entities off as they reconciled with their lost loved ones. In addition to causing trouble, Celts thought that the presence of Druids, or Celtic priests, was to help assume some things about the near future. Because of this, witches and ghosts became associated with this holiday.

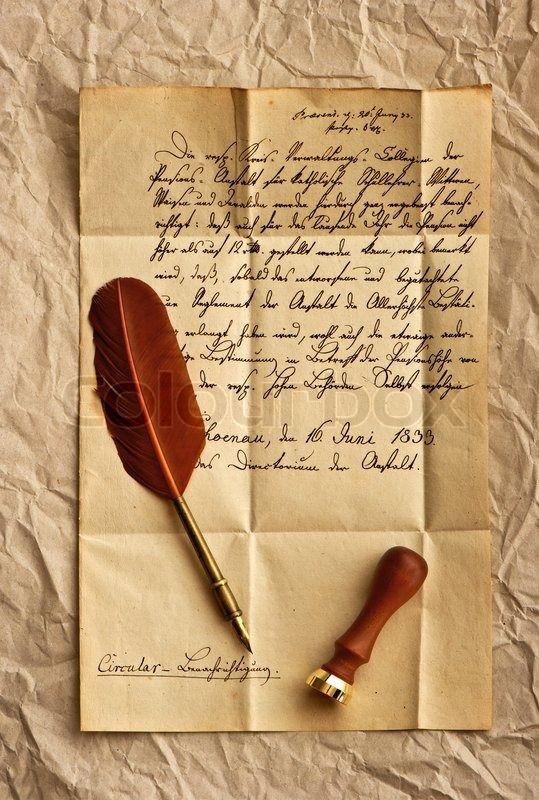

In the 7th century, Pope Boniface created a holiday known as All Saint’s Day, originally celebrated on May 13th. One century later, Pope Gregory III moved the holiday to November 1st, likely as a Christian substitute for the Pagan festival, Samhain. The day before this holiday became known as All Hallows Eve, or Halloween. This day marked the end of the summer, the harvest, and the beginning of the dark-cold-winter.

To commemorate this event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where people gathered to burn crops, and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes. When the celebration was over, they re-lit their hearth fires, which they would use to help protect them over the coming Winter. In the course of 400 years that the Empire ruled the lands, two festivals of Roman origin were created and were combined with the traditional Celtic festival of Samhain. The second day was a day to honor Pomona, a Roman goddess of fruits and trees. Pomona’s symbol is an apple, and the incorporation of the apple for Samhain is most likely why “bobbing for apples,” is something we do every Halloween.

It’s very believed today that the church was reattempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related church-made holiday. All Souls Day was celebrated almost the same as Samhain, with huge bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels, or devils. All Saint’s Day was also known as All-Hallows or All-Hallowmas (coming from Middle English Alholowmesse, meaning All Saints Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve, and eventually Halloween.

The celebration of Halloween was extremely limited in colonial New England because of the belief systems there. Halloween was more common in places like Maryland, and the southern colonies. As the beliefs and customs of different European ethnic groups and the American Indians meshed, a distinctly American version of Halloween began to rise. The first types of celebrations included, “play parties,” which were public celebrations held to celebrate the harvest. Neighbors would share stories of their dead loved ones, tell each other’s fortunes, dance and sing. Colonial Halloween festivities included telling paranormal stories, and making trouble of any and all kinds. By the 19th century, annual Fall activities were common, but Halloween wasn’t celebrated everywhere in the country. In the second half of the 19th century, America was flooded with new immigrants.

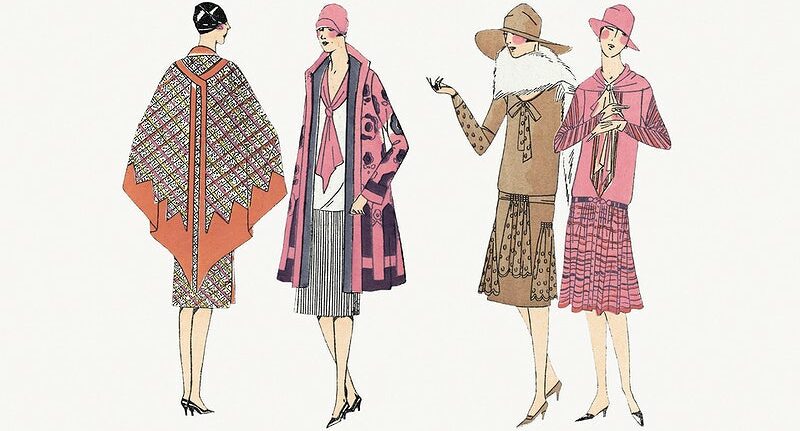

They, especially the millions of Irish flooding the Irish Potato Famine, helped to spread the holiday of Halloween across all the nation. Coming from European ideas, Americans would dress up and ask for food or money. This activity would eventually spawn into today’s trick or treating. In the late 1800s, there was an action in America to form Halloween into a holiday more focused on community and neighborly groups, rather than about paranormal entities, pranks, and candy. Around the turn of the century, celebrations or parties surrounding Halloween for both children and adults became the most used way to celebrate the holiday. These Halloween parties focused on games, foods of the season, and, most importantly, festive costumes. People who had been celebrating the holiday were pushed by newspapers and community leaders to take anything “frightening” or grotesque,” out of Halloween celebrations. Because of these actions, Halloween lost the majority of its superstitious tendencies by the beginning of the 20th century.

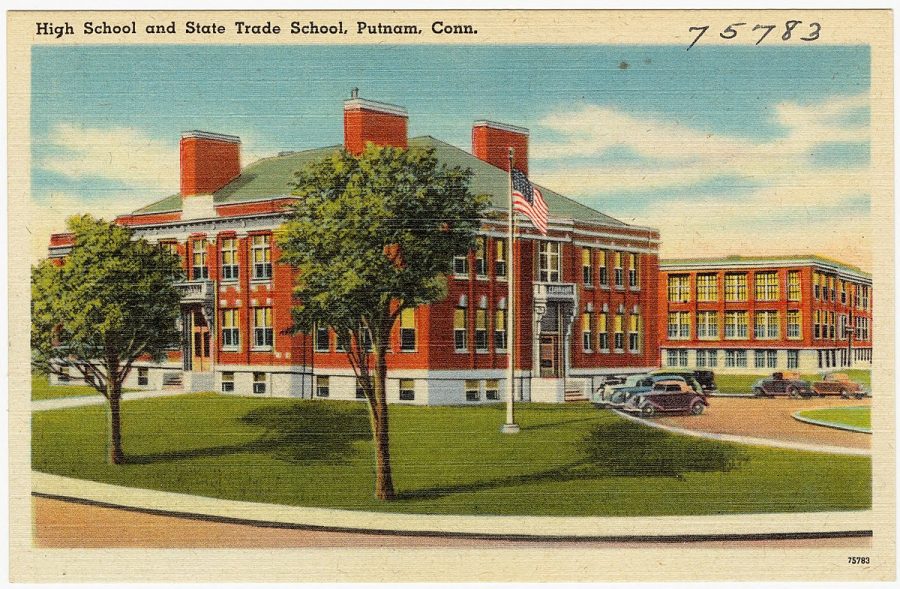

By the 1920s-30s, Halloween had become a non religious but community-wide holiday, with parades, and town-wide Halloween parties as the featured entertainment. Despite the efforts of schools and communities, vandalism began to ruin some celebrations in a lot of neighborhoods during that time. By the 1950’s, town leaders had successfully limited vandals from vandalizing anything and Halloween had evolved into a holiday directed mainly at the children. Due to how many children were being born during the fifties “baby boom”, parties moved from town civic centers into the classrooms or homes, where they could be more easily accommodated. Between 1920-1950, the centuries old practice of trick or treating was also brought back. Trick or treating was an inexpensive way of spreading the celebration of the holiday throughout the community. Children these days go trick or treating with their parent(s) until their parents decide it’s getting late and they should go home and get some sleep. Teenagers today will usually throw Halloween parties, go to bonfires, go trick or treating in groups with their friends, or go to haunted houses. Although there have been lots of changes since Halloween first became a holiday, the spirit of Halloween is still the same, if not stronger.