Credulity Is Not a Virtue

March 14, 2021

Michael “Marsh” Marshall, project director of Great Britain’s Good Thinking Society and the primary inspiration behind my article, opens his lectures intended to foster skepticism among schoolchildren exactly the way that all present school staff members expect: he spends up to 20 minutes explaining “the ten reasons to believe the world is flat, without telling the kids that [he doesn’t] actually believe the world is flat.” I applaud his approach to these lectures, in large part because for a rational individual it takes real courage to pretend to be a conspiracy theorist in front of a crowd that doesn’t know the difference. Marshall’s reasoning behind the structure of his lectures revolves around the knowledge that “it’s not interesting to learn about principles,” and that the better way to get people’s attention is with a hot-button issue (never mind how remarkable it is that the shape of the Earth is a hot-button issue for some people in the year 2021). Once all ten arguments in favor of the flat Earth theory have been established, Marshall guides his listeners through all of the rules of physics that disprove each one, at which point it is safe to introduce the aforementioned principles – principles of (in)validating an argument or a source – because they will be immediately applicable.

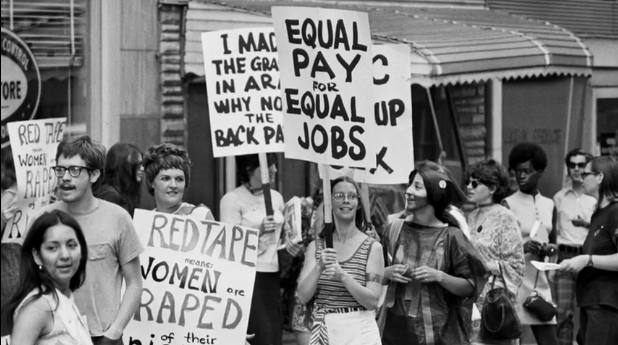

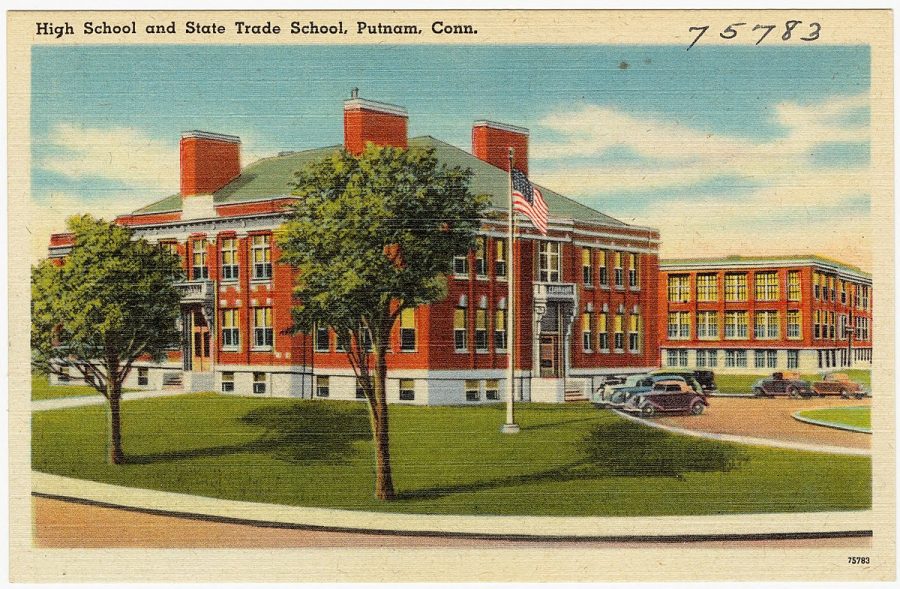

All of this is to say, I would absolutely love to see History and English teachers here at Forest Grove High School approach their respective lessons on propaganda and media literacy as though they were Michael Marshall. While I appreciate that my APUSH class examined not only the messages of propaganda created during various wars and revolutions but also the tactics used to convey their messages, I would appreciate the class a lot more if it also took the time to examine those same tactics as they appear in present-day propaganda. I’m grateful that our English curriculum includes media literacy and the breakdown of logical fallacies, and even more so that my teachers have been willing to explicitly call out the far right throughout the last three years, but I’ve also noticed that we aren’t usually given opportunities to decide for ourselves which sources have which bias. Instead, we’re told ahead of time who is “leftist,” who is “on the right” and who’s most moderate, and then assigned to analyze the logical fallacies each source contains. This reminds me of my other favorite quote of Marshall’s: “If you just go in and say, ‘Here’s a list of things that are bullsh*t,’ then you’re just priming kids to fall for the next thing that’s not on that list.” Given that the list continues to grow and expand, it’s important that people learn from a young age to treat any new information with skepticism.

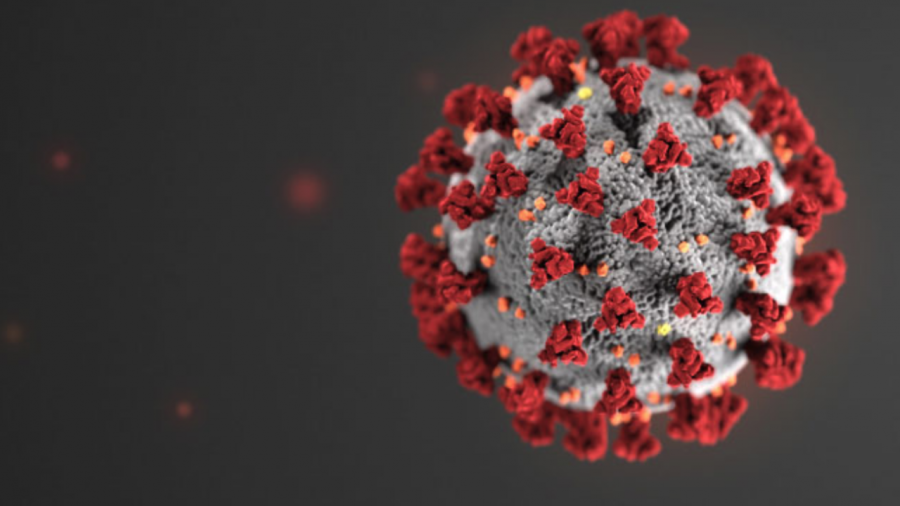

At the top of “that list” at this very moment are the QAnon sponsored conspiracy theories, unless, of course, we’re considering a list created by the QAnon Shaman himself, in which the first thing on that list is just reality. Anti-vaxxers are another pervasive online presence, and I have to imagine that their success stems from their ability to publish new, equally false yet equally frightening information as soon as we can achieve herd immunity from their previous claims. In the grand scheme of the time in which people have lived, though, neither of the above “things that are bullsh*t” have had nearly the longevity nor the impact of the Church.

If you were to Google “Michael ‘Marsh’ Marshall” you would quickly discover that he is firmly against organized religion and homeopathic medicine, and that his entire career and public persona have been formed to fight these sometimes well-intentioned but ultimately harmful elements of society as a whole (as opposed to the Good Thinking Society). My assumption is that you won’t Google him, because we just aren’t taught to double-check everything, but since you very well could I refuse to dance around the fact that in my mind skepticism and critical thinking are intrinsically connected to religion in that they contradict it. I am motivated to write this article by my desire for a more secular society. I can’t help but believe that, in the words of atheist author and activist Noah Lugeons, “If you taught kids how to think skeptically, how to think rationally… kids would come home and say, ‘Hey, Mom, God doesn’t exist.’” My objections to religiosity cannot be overstated, but they are a subject for another article, so in an effort to tie this article up with a bow without going off on too many tangents I’m going to encourage you all to think critically about the thing that pushed me over the edge when it came to declaring myself an atheist, which I would like you to note is not something that was ever addressed during the comparative religions portions of our history classes nor when religious references were made by the books our English teachers assigned. Here it is in the form of a Ricky Gervais quote: “There have been nearly 3,000* gods so far but only yours actually exists. The others are silly made up nonsense. But not yours. Yours is real.”

*Yes, I know that there are more gods than that just according to Hindus. If you’d like to insert “33 million” into the original quote, that might actually make my argument even more convincing, so don’t hesitate to do so.