Gun Control: Why I Am Absolutely For It

When I was 12 years old, my father unearthed a small parcel from a locked wooden box he kept in the garage. It fit within the span of his hands, a small thing wrapped carefully in a cloth dishrag dirtied with age. When he removed the cloth, he offered me an old revolver, much older than I was and much older than he was. It had been his father’s and now it was my turn to hold it in the family hands.

When the gun landed in my hands it felt like the heaviest thing I had ever held. Not physically — this tiny gun didn’t have enough weight to pull me down with any force, none at all — but metaphorically. Metaphorically it was so heavy I thought my hands might break beneath it. The moment I touched it I wanted to not be touching it any longer — the more I ran my fingers over the cool metal, the more I thought about the Sandy Hook children.

I knew that all I would have to do is flip a switch, squeeze one finger, and I could potentially kill someone. I could be a 12-year-old murderer with enough fervor, or with enough of an accident, or with enough entitlement. And with this thought, I shoved the gun back into my father’s hands and never looked at it again.

Sandy Hook was only a year before this, and I remembered the pain I felt watching those children file out of their own school, hands above their heads, tears and snot leaking from their faces like from a faucet, an unbearable trauma already making themselves known on their tiny shoulders. I sobbed watching the news, thinking what if that was me? What if that was my school? I sobbed when it was Aurora, Colorado, and people suffocated while they were picked off, swarming to locked exits, and it took me a long time before I went to the movie theatres. I sobbed again when it was in Orlando, and the police had to walk through all the bodies strewn on the floor, everyone’s phones still ringing with loved ones on the other end hoping they would pick up, all of them sent to voicemail. And then I sobbed more when it was Parkland, Florida, and people my age, people that looked like me, stepped over their classmates lying in the hallways to get to safety, trying their hardest not to get blood on their shoes, trying not to look their friends in the eye.

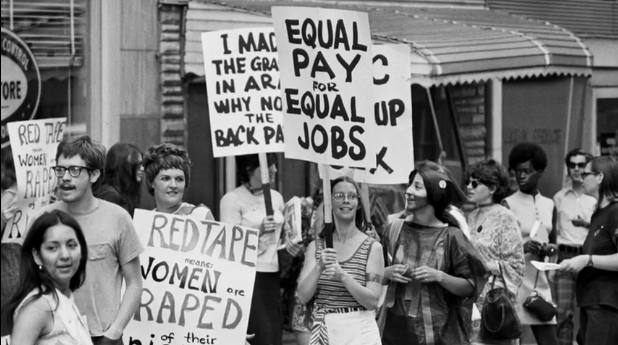

These instances of gun violence hit me with such emotional force because of how easily I could envision their pain, because of how easily I could imagine that was me, or my friends, or my family, or just about anyone I knew. It was easy because I was in the only country where I knew this kind of thing happened on the regular, and we had vigils and news stories about it, and maybe someday someone would publish a book documenting their suffering, but then the next shooting would happen and there would be more people to grieve. More white men to infantilize. More mental illnesses to blame. The guns would be coddled, read a bedtime story before they were tucked into bed by the 2nd Amendment that protected them. No other developed nation had this same infatuation.

In fact, when compared to other nations, we outrank every other developed country in terms of gun violence. So why us? Why is the U.S. experiencing what other countries with similar high-income status do not? The answer is simple: gun control. When the United Kingdom laid witness to a mass shooting of an elementary school in 1996, the gun debate didn’t last long. Nine years earlier, they had banned semi-automatic weapons in the wake of a mass shooting, and now with elementary children and staff murdered at the hands of a shotgun, those were banned as well (The Guardian), and there has now only been one shooting in the U.K. since the elementary school shooting. So when the U.S. experienced a similar shooting — one that caused 20 sets of parents to host funerals for their 1st-grade children, and 6 more for the staff that catered and taught them — why did we sit back and think there was nothing we could do? In 1996, Australia dealt with the aftermath of the Port Arthur massacre, which left 35 dead and 23 seriously wounded, with strict new registration and a national firearm buyback. These regulations and new policies cut gun-related deaths and injuries by more than half. These are countries similar to the U.S. in income, in status, and an issue — and these policies worked. The truth is that the U.S. is better at making excuses than in making change.

The argument against gun control is feeble at best — and mostly because the alternatives they ask for are examples of gun control. Background checks are forms of gun control. Gun education is a form of gun control. They are not alternatives to the radical — they are steps that pave the way for change. Educating people about how to safely use and diffuse guns cannot be in place of gun regulation, because that’s the first step to gun regulation. Those alone don’t do any justice. Those paired with registrations, minimum banning, and policy upheaval do justice. This isn’t to say all guns are to be bought back by the government and no one can ever touch one ever again — the argument was never to take guns away from responsible gun-owners. But often the lead gets lost when we are trying to decide who really is a responsible gun-owner, especially when this was never an attribute required to own a gun. Hunters and farmers (with appropriate background and aptitude testing) don’t make me worried for my safety — people that own semi-automatic rifles, for fun or otherwise, do.

When it comes down to it, I’m scared. I go to school always knowing where my exits are, in case someone with a gun decides it’s just not their day today. I am intensely aware of every way someone could enter any building I’m in with a gun, and where I would hide, who I would risk my life for, how I would escape. I’ve drafted the text I would send to my mother a million times, cataloging everything I needed to say before I stared down the barrel of a gun. All the facts and statistics in the world do not compare to the simple fear I, and many others, feel when the issue of gun control is debated. This is what makes change a necessity to me — that I fear for my life because someone can legally obtain a device suited for killing.

At 12-years-old I was scared of guns, and five years later I am still scared, with more evidence of death to back up my claim. If anything, I become more and more terrified as the years go on, as we lay witness to death and destruction and continue to tell ourselves it is a mental health issue, or simply just not our problem. I’m for gun control because of Orlando, and because of Sandy Hook, and Columbine, and Parkland, and San Bernardino, and Las Vegas, and Aurora. I’m for gun control because that could have been me — it could have been you. More importantly, if we don’t make a change in the way we think about guns, that will be me, and it will be you.

Jessie Shepard is the Section Editor of the Resources section of the Advocate. She is a senior at Forest Grove High School and is very excited to graduate...

Belinda Church Hanley • Oct 24, 2018 at 8:21 am

Thank you for this powerful essay. As a 67 year old, I do not have your perspective. You and other young people give me hope for the future.