Amelia Mary Earhart was born to Samuel “Edwin” Stanton and Amelia “Amy” Earhart on July 24th, 1897. Amelia had two siblings: Grace Muriel, and one stillborn the year before her birth. Amy Earhart did not want to raise her kids as “nice little girls,” so Amelia and her sister’s childhood was seemingly unorthodox. She was a very adventurous child who was constantly climbing trees, hunting small animals, and using a sled downhill. She was taken to the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines and described a plane she saw as “a thing of rusty wire and wood and not all that interesting.”

Amelia and her sister moved in with their grandparents in Atchinson while their parents moved into a smaller home. They were being homeschooled at this point. The family was reunited in 1909 and the sisters were placed into public school, with Amelia entering 7th grade. Despite their lives seemingly getting better with purchasing a new house and hiring two servants, Edwin was becoming an alcoholic. He was later forced to retire from his job and he did attempt to go to rehab but was not given his job back. Amelia Otis, Earhart’s grandma, suddenly died and left an estate that put her daughter’s share into a trust, as she feared Edwin would spend all the money on alcohol. Unfortunately for the family, the Otis household and everything inside was auctioned off. This situation left Amelia broken-hearted, and she described it as “the end of her childhood.” She then began attending Central High School as a junior, since her father had finally found a job as a clerk at Great Northern Railway in St. Paul, Minnesota. He applied to be relocated to Springfield, Missouri, but the current worker changed his mind regarding his retirement and wanted his job back, which left Edwin with nowhere to work.

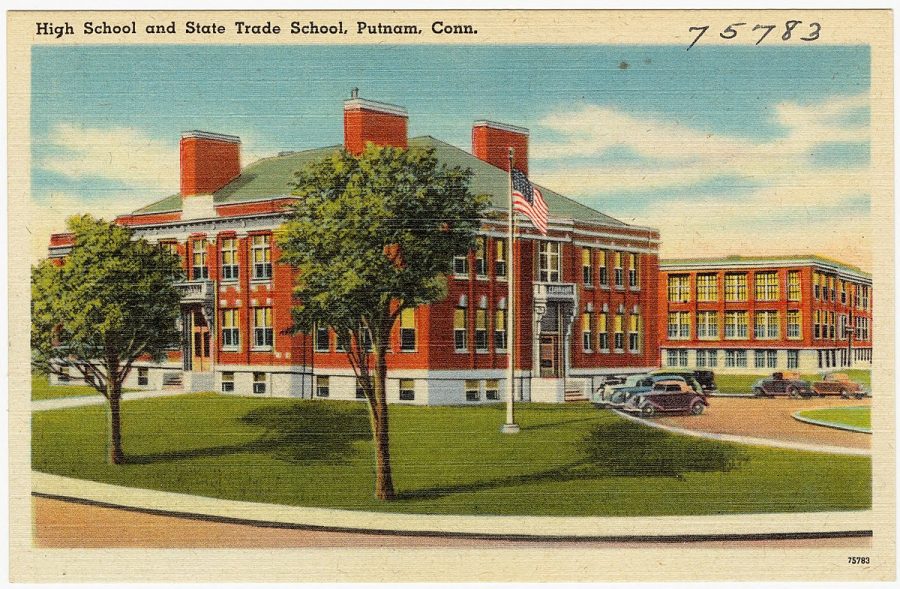

Amy Earhart then took her kids to Chicago to live with some friends, as they were nearing another disastrous move. Earhart made the abrupt decision to search for a high school with the best science program. The nearest school to her house was just not decent enough for Amelia. She refused to go because the chemistry lab was “just like a kitchen sink.” She enrolled in Hyde Park High School but spent one semester there. In the yearbook photo captioned “the girl in brown who walks alone,” one could gather how she felt. She graduated from Hyde Park in 1916. Amelia then began junior college at Ogontz School in Rydal, Pennsylvania, but never finished. While on vacation in 1917, Earhart visited her sister in Canada. WWI was at its peak by now, and Amelia saw the injured soldiers returning from war. She received nurse’s aide training from the Red Cross and worked with the Voluntary Aid Detachment at Spadina Military Hospital. Her responsibilities included preparing food for patients with different diets and handing out prescriptions. Amelia developed an interest in airplanes and flying while hearing stories from military pilots.

When the Spanish Flu pandemic hit Toronto, Earhart was involved in nursing duties that included night shifts at the hospital where she worked. Amelia later came into contact with the disease and was hospitalized for pneumonia and sinusitis in November 1918, but was discharged in December. She continued to have symptoms until a few minor operations were performed, which were unsuccessful. In 1919, Earhart was preparing to go to Smith College; however, she changed her mind once more and chose to enroll in medical studies at Columbia University. She quit a year later as her parents had rekindled in California. Earhart and her father went to an aerial meet, where she requested him to ask about flying lessons. She was booked for a passenger flight the next day and mentioned after the flight that by the time they got 200-300 feet in the air, she knew she needed to fly. Earhart hired a flying instructor the next month named Neta Snook by working several jobs and saving money. Her first lesson was on January 3rd, 1921 at Kinner Field.

During this time, Amelia cut her hair to resemble other female pilots and purchased a used chromium yellow Kinner Airster biplane, which she named “The Canary.” On October 22nd, 1922, Earhart flew her plane to an altitude of 14,000 feet, which set a world record for female pilots. 7 months later, Amelia became the 16th woman in America to gain a pilot license. Throughout this, Amelia’s inheritance gained from her grandmother would slowly diminish after she made an investment that later failed. She then sold The Canary and another Kinner and purchased a yellow Kissel Gold Bug “Speedster” two-seat car, which was named the “Yellow Peril.” Right around the same time, she began experiencing a rekindling of her previous sinus issues. The pain only got worse and in 1924, she was hospitalized once more for another operation, which failed again. In the time after her parents’ divorce, Amelia drove her mother down from California to Banff, Alberta, and then to Boston, Massachusetts.

Earhart received a successful sinus operation there. She returned to college before being forced to unenroll and forget any plans because it was no longer affordable. Not long after, Amelia received a job as a teacher, and then a social worker at a Boston settlement home, She became a member of the American Aeronautical Society in Boston and later the vice president. Amelia also flew the first official flight out of Dennison Airport in 1927. After Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, Amy Guest, the daughter of American industrialist Henry Phipps Jr, was interested in being the first woman to do so. The trip was decided to be too dangerous for her so she said she’d sponsor and find the girl with “the right image.” Earhart then got a call while at work from Captain Hilton H. Railey, who asked if she wanted to fly the Atlantic. She agreed and got on the plane with Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon. The three left Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland on June 17th, 1928, and landed in South Wales 20 hours and 40 minutes later. A blue plaque remains there, honoring her. In July 1936, a Lockheed Electra 10E was created with specific edits requested by Amelia, including several more fuel tanks. She chose Captain Harry Manning as her navigator. The original plan was a two-person crew, Amelia and Manning.

However, Manning had made a few navigational corrections that were incorrect and put the passengers in the wrong place during other flights, so he was replaced with Fred Noonan. After repairs and test flights gone wrong, Amelia and Noonan took off on July 2nd, 1937 at 10:00 AM in the Electra with 1100 gallons of fuel on board. The intended destination was Howland Island. At around 3:00 PM, Earhart reported that the current altitude was 10,000 feet, and later at 5:00 pm, reported as 7,000 feet. During the approach to their destination, strong and clear signals were received from Earhart, but she couldn’t hear anything. The first calls from her discussed weather conditions and then how they had about half an hour of fuel left. Another radio log revealed that they thought they were near the destination but couldn’t find it, and the altitude was 1,000 feet. Earhart’s earliest call stated that she couldn’t hear anything and it was determined that they had to have been in the immediate vicinity due to how loud the call was. Morse code was sent instead and Earhart said she received these but couldn’t find their direction. After all contact was lost with Howland Island, operators across the Pacific and United States may have heard signals from the Electra but they were either not understandable or weak.