Change Edition – Mental Health & The Dehumanization of Athletes

Image via The Boston Globe

March 2, 2022

Content Warning: Mentions of Suicide, Death, Sexual Abuse, Self Harm, and Drug Abuse

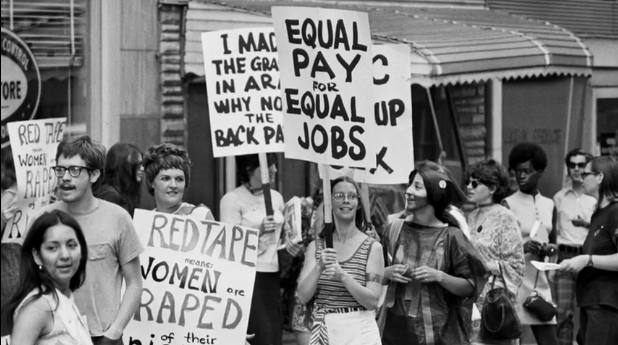

On November 8, 2021, sports agent Rich Paul reported that Philadelphia 76ers all-star Ben Simmons’ mental state declined after the hate and controversy sparked after his trade request during the summer, and he was unfit to play. Surprisingly, this was met with doubt and ignorance. Many fans and sports commentators called Simmons out for this, a scene sadly not too uncommon in the last few years. Ben Simmons being told to “shut up and play” is only the most recent, in a seemingly never-ending story of athletes being criticized and torn down for their mental health.

Athletes having mental struggles is only a relatively new subject in the public eye. The first widely known example of this was in 1993, when Detroit Pistons star, Dennis Rodman, was found in The Palace of Auburn Hills parking lot with a loaded rifle in the passenger seat of his truck, contemplating suicide (Bad as I Wanna Be, 1997). While Rodman became one of the most famous NBA Players of the 90s, many others weren’t given the same spotlight. Delonte West is an example of one. Delonte West was a rotation guard on a few NBA teams in the mid to late 2000s, notably the Boston Celtics and Cleveland Cavaliers. West grew up in a poor household, experienced depression at a young age often self-harmed, and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2008 while a member of the Seattle SuperSonics (washingtonpost.com, 2015). In 2010, a rumor circulated that West had an affair with Gloria James, fellow Cavaliers LeBron James’ mother. This rumor ruined West’s reputation, and he was out of the league within years. West spiraled into drug addiction and homelessness. West cried out into deaf ears for years, only reappearing in headlines whenever new videos or photos of him panhandling or walking the streets in hospital gowns were sent to TMZ. Thankfully, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban let him stay in his house and even got him a job at an addiction clinic in 2020 (SI.com, 2020).

Athletes being open about their mental health has only been around since the mid-2010s, thanks in part to players like DeMar DeRozan, Kevin Love, and Larry Sanders. Despite this progressing awareness and acceptance of mental health, many fans and reporters still shun players for being open about their experiences. During the 2020 Olympics, Conservative Commentator Charlie Kirk said Simone Biles was a “disgrace to the country” for withdrawing from the Women’s Gymnastics Team due to fear of injury as well as mental illness (Newsweek.com, 2020). Last year, Skip Bayless called Dak Prescott weak and a poor leader for opening up about his struggles with depression after his brother’s suicide (washingtonpost.com, 2020). The reason people say these things about athletes talking about their mental illness has nothing to do with acceptance or awareness of mental health. They are actively dehumanizing these people. Professional Athletes are nothing more than Madden or 2K characters in real life to a sadly large camp of people. Players are only there for their entertainment. Only recently were NCAA athletes awarded the rights to their likenesses after decades-long legal battles (NCAA.org).

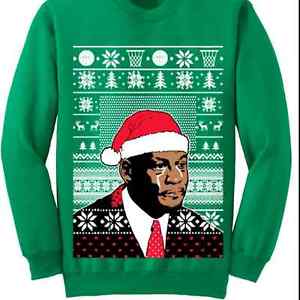

Ben Simmons isn’t getting hate because he’s a man struggling with anxiety; he’s getting hate because he isn’t playing basketball games (and playing in Philadelphia, one of the worst sports fanbases in the United States, isn’t helping). To many, it is “unprofessional” to exemplify strong human emotions as a professional athlete. Serena Williams was called “childish” after getting upset with an umpire who called a penalty on her (abcnews.go.com, 2019). Cam Newton was called “unprofessional” after being upset and walking out of a press conference after losing the Super Bowl (nfl.com, 2016). Kyrie Irving was called “lazy” after sitting out of the bubble to protest police brutality (sbnation.com, 2020). Kwame Brown was called a “bust” after being abused and bullied by Michael Jordan during his first seasons (YouTube Channel: Kwame Brown Bust Life, 2021). These players are people. Many still look down upon even sitting out due to fear of injury. There are countless stories of players getting addicted to opioids to play through the pain in the NHL (adalanterecovery.com, 2021). In sports like baseball and hockey with multi-layered minor leagues, you’d want to squeeze out any potential you have to stay at the top and not get left behind. This is why players will sometimes intentionally hide injuries for too long or until it’s too late, just to stay on a roster. CTE in The NFL is a whole different story altogether (pbs.org, 2013). Just for reference, the NFL only established the Concussion Protocol in 2009, when players had started reporting symptoms of CTE as early as 1906 (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, 2014). The NFL even denied and covered up the existence of brain injuries caused by head-on collisions for years to paint themselves in a positive portrait.

Owners and coaches can often be held at fault for this since they don’t want to have any possible risk of losing or ruining the team’s reputation. In 2010, the Chicago Blackhawks did not file a report or fire a coach for sexually assaulting multiple players out of fear that their playoff run would be tainted by controversy. Former Los Angeles Clippers owner and longtime racist, Donald Sterling, saw his team as a plantation (slate.com, 2014), wanted “poor black boys from the south and a white head coach” on his team (vox.com, 2014), and almost axed a trade for J.J. Redick because he was white (cbssports.com, 2020). Jordan McNair, a 19-year-old Offensive Lineman for the Maryland Terrapins, died of a heat stroke during practice after his coaches wouldn’t allow him to rest (SI.com, 2019). Too often, we see these people treated like workhorses to coaches and owners for profit. We’ve heard too many stories about NCAA and High School coaches abusing and belittling their players (insider.com, 2020). It’s dog-eat-dog in the sports world, and players are disposable to the big guys on top.

The mistreatment of these people just because they’re good enough at shooting a basketball has gone on for too long and needs to change. Players like Steve Montador shouldn’t have to play through a concussion just to keep their jobs (cbc.ca, 2020). Ben Simmons shouldn’t have to face criticism and skepticism when opening up about his personal mental struggles. This mentality of fans and owners over players has dominated the sports world for generations, and significant change needs to be done before it gets worse. While the previously mentioned Mental Health Awareness Movement in the last decade has improved many stigmas against professional athletes, too many people reject that and opt for the “Old Boys’ Club” (nbcsports.com, 2021) mentality of the past. I’ll end this article off with this; the worst thing that could happen to Ben Simmons, Calvin Ridley, and Simone Biles for potentially faking having a mental illness is that they don’t play a sport, that’s all. The worst thing that could happen to them if they have a mental illness is ten times more serious than any of that.